As the end of National Poetry Month approaches, I want to introduce to John Henry Newman Beecher.

John Beecher has been called a political poet, the everyman’s scribe. Frank Adams, in the magazine “Southern Exposure,” once wrote:

“John Beecher was a radical poet, perhaps America’s most persistent

for 50 years,The heir of an Abolitionist tradition and proponent of the

dispossessed seizing of power. His most enduring lyrics are about the

downtrodden’s fight for economic justice, human dignity and political

freedom. He heard the music in their voices with uncanny accuracy.”

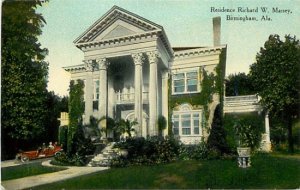

Born in New York City on January 22, 1904, Beecher was three when his father, who was an executive for U.S. Steel, was transferred to Birmingham. When Beecher graduated from high school (at age 14), the elder Beecher put him to work in one of the steel mills until he became old enough to enter the military.

Beecher finally enrolled at Virginia Military Institute in 1919, but that experience did not last. He soon found his way back to Birmingham and its mills. During this second stint in the mills, Beecher worked 12-hour shifts.

Later Beecher left for Cornell to study engineering. While there, an English instructor, William Strunk, Jr. (Yes, that William Strunk, Jr.) took interest in Beecher’s poetry. Adams wrote, “He quit Cornell to return to the steel mills and writing. Eventually, he finished college at the University of Alabama in 1925, and that summer went to Middlebury College’s Bread Loaf School of English, where he studied with Robert Frost.”

Beecher later returned to the mill but was severely injured. Beecher had probably already known that working in a mill could be hazardous to his health, but after his injury he penned poetry that spoke of the dangers and management’s overall dubious behavior. His “Report to the Stockbrokers” illustrated these points:

I.

he fell off his crane

and his head hit the steel floor and broke like an egg

he lied a couple of hours with his brains bubbling out

and then he died

and the safety clerk made a report saying

it was carelessness

and the crane man should have known better

than not to watch his step

and slip in some grease on top of his crane

and then the safety clerk told the superintendent

he’d ought to fix the guardrail

II.

out at the open hearth

they all went to see the picture

called Men of Steel

about a third-helper who

worked up to the top

and married the president’s daughter

and they liked the picture

because it was different

III.

a ladle burned through

and he got a shoeful of steel

so they took up a collection through the mill

and some gave two bits

some gave four

because there’s no telling when

IV.

the stopper-maker

puts a brick sleeve on an iron rod

and then a dab of mortar

and then another sleeve brick

and another dab of mortar

and when has put fourteen sleeve bricks on

and fourteen dabs of mortar

and fitted on the head

he picks up another rod

and makes another stopper

V.

a hot metal car ran over the Negro switchman’s leg

and nobody expected to see him around here again

except maybe on the street with a tin cup

but the superintendent saw what an ad

the Negro would make with his peg leg

so he hung a sandwich on him

with safety slogans

and he told the Negro boy just to keep walking

all day up and down the plant

and be an example

VI.

he didn’t understand why he was laid off

when he’d been doing his work

on the pouring tables OK

and when with less age than he had

weren’t laid off

and he wanted to know why

but the superintendent told him to get the hell out

so he swung on the superintendent’s jaw

and the cops came and took him away

VII.

he’s been working around here since there was a plant

he started off carrying tests when he was fourteen

and then he third-helped

and then he second-helped

and then he first-helped

and when he got to be almost sixty years old

and was almost blind from looking into the furnaces

the bosses let him

carry tests again

VIII.

he shouldn’t have loaded and wheeled

a thousand pounds of manganese

before the cut in the belly was healed

but he had to pay his hospital bill

and he had to eat

he thought he had to eat

but he found out

he was wrong

IX.

in the company quarters

you’ve got a steel plant in your backyard

very convenient

gongs bells whistles mudguns steamhammers and slag-pots blowing up

you get so you sleep through it

but when your plant shuts down

you can’t sleep for the quiet

Beecher’s poetry also pointed to discrimination outside the mill. Beecher wrote about the hypocrisy of the city’s racially-motivated bombings in “If I Forget Thee, O Birmingham!”

I.

Like Florence from your mountain.

Both cast your poets out

for speaking plain.

II.

You bowl your bombs down aisles

where black folk kneel

to pray for your blacker souls.

III.

Dog-town children bled

A, B, O, AB as you.

Christ’s blood is not more red.

IV.

Burning my house to keep

them out, you sowed wind. Hear it blow!

Soon you reap.

Beecher attended Harvard from 1926-1927. He also attended the Sorbonne, University of Wisconsin, and the University of North Carolina.

A quest for fairness for all people drove Beecher’s actions and art, said Foster Dickson during a telephone interview. Dickson is a Montgomery educator who has written a book on John Beecher’s legacy. “John Beecher came from a long line of people who strove to do the right thing – Lyman Ward Beecher, Henry Ward Beecher, and Harriet Beecher Stowe. He had a passion for protesting unfairness,” he said.

In addition to using poetry as a weapon of protest, Beecher also wrote prose and worked on FDR’s Fair Employment Practice Committee to investigate discrimination. Beecher worked as a journalist and anthropologist, too.

He suffered consequences, as “If I Forget Thee, O Birmingham!” alludes to. He was investigated by the House Un-American Activities Committee, and in 1950, Beecher refused to sign California’s state loyalty oath and was fired from his position as a sociology assistant professor at San Francisco State College.

Beecher briefly returned to Birmingham in 1967 as Miles College’s visiting professor of creative writing.

Foster Dickson is disappointed that Beecher’s work, especially his poems, has been essentially forgotten. In fact, Dickson’s book, “The Life and Poetry of John Beecher (1904-1980),” criticizes keepers of the “canon” for ignoring Beecher. But as Frank Adams wrote in “Southern Exposure” magazine, Beecher did not write to be praised by his literary peers. “Like Isaiah, or Bunyun, and even Sandburg for a time, his poems were for average people. Beecher seemed to know instinctively that poetry was not just for critics, but that people used it in one way or another every day, not to flatter but to survive…The poet’s task was to listen, to record, then to chant his poetry.”

On May 11, 1980, Beecher died of lung disease in San Francisco.

Want to know more about John Beecher? Click this link.

Have you already heard of Beecher before reading this piece? If so, what’s your favorite Beecher poem? Leave a comment, please.