My grandmother – and Bob Dylan – used to say “I’ve forgotten more than you’ll ever know.” I’m not sure if that’s true of Dylan, but I believed my grandmother, a life-long student who died days shy of her 92nd birthday.

If James L. Baggett, head of the Department of Archives and Manuscripts at the Birmingham Public Library, told me that, I’d believe him, too. How could I not? He has worked almost 20 years among more than 30,500,000 documents, photographs and drawings, and other artifacts. And if you’d ever been blessed to attend one of his walking tours, then you know he could rattle off a timeline on Birmingham history in his sleep.

I recently spoke with Baggett in his basement office at the Central Library. You can join the conversation below.

Are you from Birmingham?

James L. Baggett: Yes, I was born here.

Where did you attend college?

UAB and Alabama. I received my bachelor’s and master’s in history at UAB, and at Alabama I did a Master of Library Science.

How did you become interested in what you are doing now, in archival work?

Sort of by accident. I was a history major at UAB and when I entered the master’s program, I thought I was going to do a straight history master’s, but they offered a public history program, which is about archives, museum management, historic site management. So I did the public history master’s and interned down here with Marvin Whiting who was my predecessor. And then I entered the Ph.D. program at Ole Miss. I thought I wanted to be a history professor, and I found I didn’t like it. I didn’t enjoy teaching. I had really enjoyed archives so I came back. I was lucky enough to get a job here and I did the library master’s. I never regretted it.

Did you like Oxford at all?

I liked Oxford a lot. I really liked living there. I liked Ole Miss and I’m glad I went. I finished the classwork; I learned a lot. I just realized the academic world just wasn’t where I wanted to be.

Does it get pretty lonely as an archivist?

Not really. Well, it depends. It doesn’t here. You know there are a lot of archivists who are known as lone arrangers, and they are “one-person shops.” That might get kind of lonely. Down here we have a full-time staff of five. We always have interns, volunteers. So at a given time we’ll have anywhere from six to 10 people working down here. And we serve 150-200 researchers a month so it’s a pretty heavily used collection.

A number of authors have given your department “a shout out” because of your assistance.

There are now more than 300 books that have been published out of this collection. That includes five winners of the Pulitzer Prize. And the last time I counted, there have been over 50 documentaries and film productions researched here, and that includes one winner of the Academy Award, Emmy Award winners, and Peabody winners. There have been at least 30 museum exhibitions researched here. But then you know, we also serve local college students and people researching a house or a building so it’s a broadly used collection.

So, what does the collection consist of, what do you house down here?

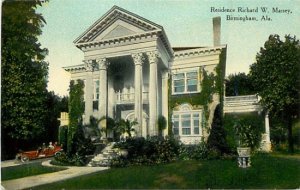

We have a variety of things. We focus on the Birmingham area, but within that, it’s a pretty broad collection. We’re the archives for the city so we house city records of historic value. We have papers of the mayors from George Ward to Richard Arrington. We serve as the archives for a lot of local organizations like OMB and the Chamber of Commerce, the YMCA, YWCA, the League of Women Voters, a lot of local clubs. We have company records, family papers. We have the largest collection in existence on the civil rights movement in Birmingham. We have the largest collection on women’s history in Birmingham. We have something in the neighborhood of 30,000,000 documents and half a million photographs.

Of course, you know, when we talk about archives, we’re talking about letters, diaries, notebooks, maps, blueprints, office files, church registers – pretty much anything you can think of, you can use to record information.

What’s the most unusual thing you’ve come across in the collection?

Probably fragments from the second Bethel Baptist Church bomb.

That’s my church, actually.

The second bomb, you know the one Will Hall [one of the men who voluntarily guarded the church] picked up and carried out into the streets, we found its fragments in the Birmingham police files. We found metal fragments of the bucket the bomb was placed inside of and pieces of shrapnel from that bomb. Some of those are now on display at City Hall.

How do you keep everything catalogued?

We inventory things at a file level. We can’t inventory all the documents. There’s tens of millions, there’s just no way to do that. So we create finding aids. It’s a guide to a collection that will list each file and tell you what’s there. We try to give a researcher a good general idea of what’s in a collection so they can know which files they might need to look into and which files they could pass over.

What’s your favorite thing about your work?

I guess there are several. Working with researchers is one. People come in with really interesting ideas, really interesting projects, and we find out how we can use our collections in ways that have never been thought of. It’s always fun to start with the research in the beginning, and when it’s done, they produce a book or an article or a Ph.D. dissertation. And finding new collections is fun.

If you could categorize the focus of the researchers, what would it be?

The biggest would be local architecture and historic buildings, and in that you would include land use. In a normal month, we’d have about 100 people come in doing either land use or historic building research. Civil rights is probably the second, especially right now with the 2013 anniversary coming up. We are getting a number of requests.

One thing I try to do when I talk to students is interest them in the other subject areas that are down here. We have lots of material here that’s just not used. With students, I ask do we need another paper on the Black Barons or the Father Coyle murder or would you like to do something new and different.

Have you ever thought about writing a book [Baggett is the author of five books] on one of those unrecognized subjects?

I’ve been working for 10 years on a biography of Bull Connor so I don’t know if unrecognized is the word – barely understood would be a better term. As much as Connor’s been written about, he hasn’t been written about in any complexity. I’m looking at him as a political figure, not just his civil rights study. I’m trying to understand him in a way no one has done.

Are you trying to show him in a more compassionate light?

It’s to try and help the reader understand him. They’re still not going to like him, and they are not necessarily going to be sympathetic to him, but I hope when I finish this, readers will come away with a better understanding. What you find when you start looking at figures like Connor, is how like us they are. Connor loved his family and he took his grandson on vacations. He was a complete person, which is what has never been explored with him before.

We want people like Connor to be totally different from us. We want to keep our distance. I find people get very uncomfortable when I talk about him and they often think I’m defending him when I’m not. I’m just trying to understand him.

On the talk you’d be giving [this evening] on Louise Wooster [Birmingham’s most famous madam] and John Wilkes Booth, did they actually have a love affair?

It’s possible. Clearly, Lou embellished the story over the years. It is possible that they could have met and had some sort of relationship. Booth was in Montgomery in 1860 for six weeks, performing. And Lou was working in a brothel in Montgomery at that time. And Booth is known to have frequented brothels, so they both were in the right place at the right time. There could have been an encounter or a brief relationship. She would have been in her late teens at that time, and Booth was a huge star. It would be like having an affair with Brad Pitt now. Now the stories Lou tells later are clearly made up because she turns it into some great love affair. It simply didn’t happen.